The Challenging Complexity of Indigenous Knowledge in Modern Conservation

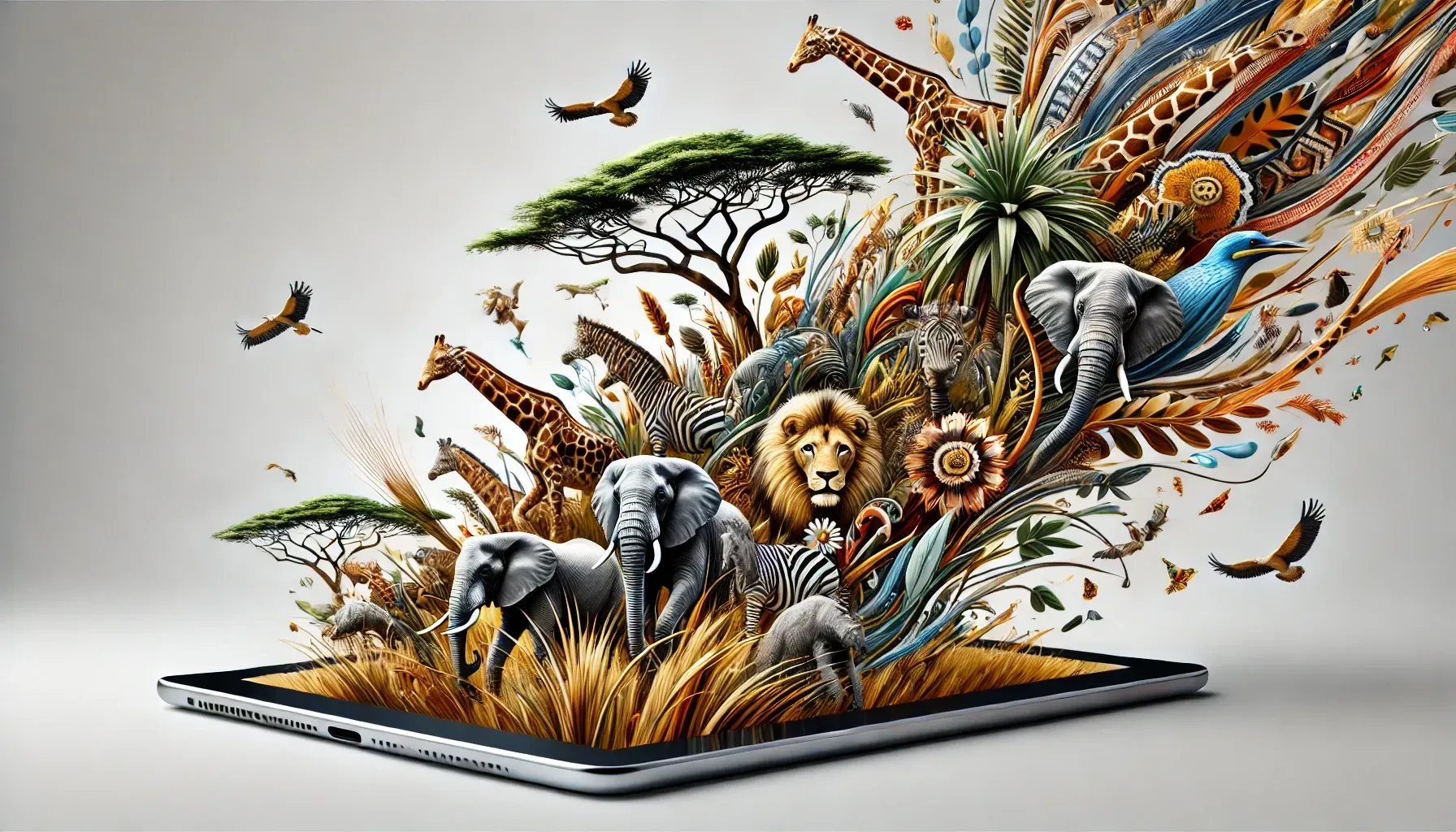

In recent years, the integration of Indigenous knowledge with modern technologies has gained traction as a promising new avenue in conservation.

From safeguarding biodiversity to managing natural resources, the narrative surrounding Indigenous practices often paints a picture of harmony with nature - a romanticized vision that can obscure the complex realities on the ground.

The truth is, Indigenous knowledge systems are not monolithic, nor are they universally in tune with nature as is often portrayed. Indigenous communities, like all societies, are diverse and adaptive. They do not live in a timeless bubble of traditionalism, but rather in a dynamic context shaped by contemporary realities, technological advancements, and external pressures. So, as we seek to integrate Indigenous knowledge into conservation strategies, it’s essential to first ask: What exactly is Indigenous knowledge, and how do we assess its relevance and effectiveness in the modern world?

Defining Indigenous Knowledge: A Complicated Task

The term ‘Indigenous knowledge’ is often used as if it represents a singular, unified system of understanding. In reality, it is as diverse as the communities from which it originates. Each Indigenous group has its own unique relationship with its environment, informed by local history, geography, climate, and culture.

But how do we define what constitutes ‘Indigenous knowledge’? Is it based on practices that have been passed down over generations, or does it also include contemporary adaptations? For instance, a community that once practiced shifting agriculture might now use chemical fertilizers and machinery - does that diminish the value of their knowledge, or does it reflect an new understanding of land management?

When we talk about Indigenous knowledge in the context of conservation, we must resist the temptation to simplify it into a one-size-fits-all solution. We must also recognize that not every community’s practices are inherently aligned with conservation goals as they are defined in Western terms. In fact, some practices that were sustainable in the past may no longer be viable in the face of climate change, population growth, or environmental degradation.

Profiling and Vetting Indigenous Knowledge: How Do We Know What’s Beneficial?

One of the major challenges in integrating Indigenous knowledge with modern technologies is determining its validity and relevance to the problem that needs solving. Just as not all scientific practices are effective in every context, not all traditional practices are beneficial for modern conservation efforts. This raises a critical question: How do we vet Indigenous knowledge?

We can start by acknowledging that Indigenous knowledge, like any knowledge system, is empirical - it’s based on observation, trial, and error. But it is also shaped by cultural values and spiritual beliefs, which may not always align with modern scientific approaches. The challenge lies in determining which aspects of Indigenous knowledge can complement or enhance technological solutions, and which may be less applicable or even harmful under current environmental conditions.

For example, some Indigenous practices may involve burning or clearing land for agriculture, practices that have been sustainable in certain contexts for centuries. However, in today’s landscape where climate change has altered weather patterns and increased the frequency of wildfires, such practices may need to be reconsidered. Vetting Indigenous knowledge requires both cultural sensitivity and scientific rigor.

Who is the Target Audience?

One of the most overlooked aspects of this conversation is understanding who we are trying to benefit through the integration of Indigenous knowledge and modern technology. Are we doing this to improve the livelihoods of Indigenous communities, to enhance global conservation efforts, or to satisfy Western expectations of what ‘sustainable’ land management looks like?

Often, conservation efforts that incorporate Indigenous knowledge are framed as a win-win scenario; protecting the environment while empowering local communities. But these efforts can fall short if they are not rooted in the real, everyday concerns of the people involved. Many Indigenous communities live modern, contemporary lives and are deeply affected by the same economic, social, and environmental pressures as any other community. Conservation initiatives must therefore align with their aspirations, whether those are economic development, cultural preservation, or simply securing a better future for the next generation.

Additionally, we must be wary of using Indigenous knowledge as a token or a checkbox in broader conservation strategies. It should not be integrated solely for the sake of political correctness or to satisfy funding requirements from organizations looking for ‘local input.’ If we are to truly respect Indigenous knowledge, we must engage Indigenous communities as equal partners in the process—listening to their goals, concerns, and the realities they face.

Why Should We Go Down This Path in the First Place?

If Indigenous knowledge systems are so complex and varied, why even bother attempting to integrate them with modern conservation technologies? The answer lies not just in the potential environmental benefits but in the larger ethical implications of conservation.

Indigenous peoples have often been marginalized in global conservation efforts, their lands appropriated in the name of environmental protection, and their voices excluded from decision-making processes. Integrating Indigenous knowledge is, at its core, a form of restorative justice—an acknowledgment that these communities have a right to manage their lands and resources according to their own values and traditions.

Moreover, Indigenous knowledge offers a critical counterbalance to the dominant Western scientific approaches, which can sometimes prioritize efficiency and data-driven solutions at the expense of long-term sustainability. By combining the best of both worlds; traditional ecological practices and cutting-edge technology, we have the potential to develop more adaptive, resilient, and context-sensitive conservation models.

However, this path is not without its challenges. We must be prepared to navigate the complexities of cultural context, ensure that Indigenous communities have agency in the process, and avoid romanticizing their knowledge as inherently superior or more ‘natural.’ In short, we must treat Indigenous knowledge not as a static relic of the past, but as a dynamic, evolving system that, like all systems, must be critically examined, tested, and adapted to meet the challenges of today’s world.

Can Technology Bridge the Gap?

One of the most promising aspects of this dialogue is the potential for technology to bridge the gap between Indigenous knowledge and modern conservation efforts. But to do so effectively, technology must serve as a tool for empowerment, not replacement.

For example, tools like GIS and remote sensing can help Indigenous communities monitor environmental changes in real-time, providing them with the data they need to make informed decisions. Mobile platforms like Cybertracker can document and preserve traditional knowledge, ensuring that it is passed down to future generations. And data analytics can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of traditional practices in modern contexts, allowing communities to adapt their strategies as needed.

The key, however, is ensuring that these technologies are accessible and relevant to Indigenous communities. They should not be imposed from the outside but developed in collaboration with the communities themselves, ensuring that the tools align with their goals, values, and ways of knowing.

Final Thoughts

As we explore the integration of Indigenous knowledge with modern conservation technologies, we must challenge the romanticized narratives that often surround Indigenous practices. These knowledge systems are not universal, nor should they be treated as such. Indigenous communities, like all societies, are diverse and live within complex realities. Some practices may align perfectly with modern conservation goals, while others may need to be reexamined or adapted.

The path forward is not about choosing between Indigenous knowledge and modern technology—it’s about creating a space where both can coexist and inform one another. By fostering collaboration, critical examination, and cultural sensitivity, we can develop more nuanced, effective, and equitable approaches to conservation.

Defining Indigenous Communities

In this context, an Indigenous community refers to a group of people who are the original inhabitants of a particular region and have a longstanding cultural, social, and spiritual connection to their ancestral lands. These communities are often distinguished by their unique languages, traditions, and knowledge systems, which have been passed down through generations and are intricately tied to their specific environment.

Indigenous communities may identify themselves based on shared heritage, cultural practices, or distinct governance structures that are typically aligned with their historical ties to the land. They may also hold collective rights to certain territories or resources, and their social structures often include traditional leadership roles and community-based decision-making processes.

About The Author

Johann brings two decades of expertise in technology seamlessly interwoven with a passion for conservation and development. His career reflects a drive for the confluence of these ideas through projects across the African continent.

Quicklinks